“Nothing can be a work of art which is not useful; that is to say, which does not minister to the body when well under command of the mind, or which does no amuse, soothe, or elevate the mind in a healthy state.”

William Morris, 1879.

Museums have benches. They are not ubiquitous but rather strategically placed. Exhibition designers put these benches where they know visitors will slow down along their path and remain in place longer. They are placed in those specific spots where an artwork calls out to the visitor, demanding to be contemplated. The benches are for them.

I never miss a good Museum when traveling abroad. Whether it is Del Prado, the Louvre, or any other, the scene is recurrent: cellphone-on-a-stick wielding crowds blindly pass by art to get a vacation-justifying selfie with the Mona Lisa or any other must-see museum star. Few visitors choose to escape the flow of the frenzied crowd. This kind of flyby museum experience is a well-known phenomenon, shaped by a complex set of cultural and sociological factors. What is more intriguing, however, is the behavior of those casual museum visitors who defiantly stop en-route and sit or stand transfixed in front of a piece of cloth daubed with colorful oleous concoctions dozens or hundreds of years ago. Even when the picture’s themes or the painter’s title may mean little to this casual beholder, a powerful connection has been made between the artwork and the viewer’s mind.

Selfies with the Mona Lisa - Louvre Museum -

Selfies with the Mona Lisa - Louvre Museum -

Connected to art - Louvre Museum -

Connected to art - Louvre Museum -

Benches may also have other uses - Louvre Museum -

Benches may also have other uses - Louvre Museum -

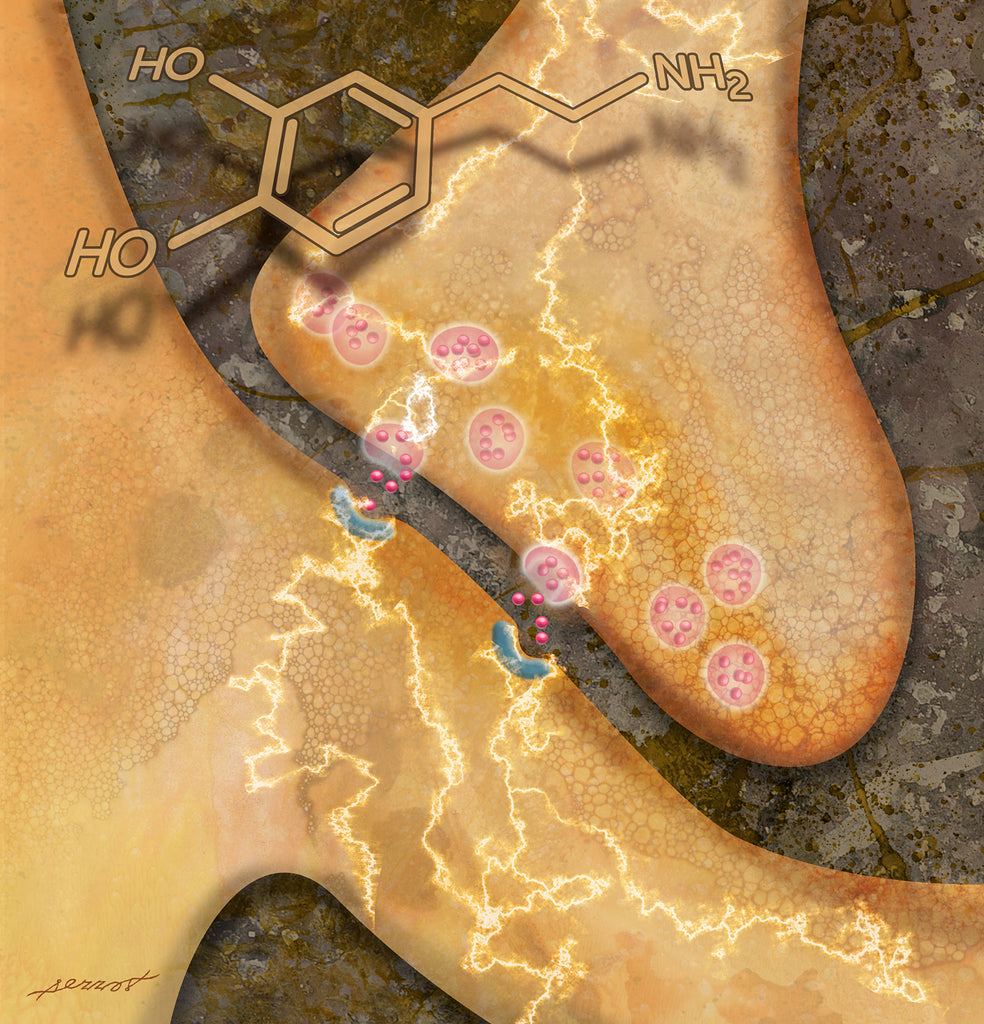

The culprit is a molecule: dopamine. Not an inconsequential molecule by any means. In recent years, its name has been abused and misused by trendy pseudoscience. And yet, there is no question that it is a key component in the system within our brain that has a lot to do with us being and becoming human.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter, a member of the chemical group known as catecholamines. Our own bodies produce the molecule. Our digestive system breaks down protein-rich foods such as meat, dairy, beans into their component parts. Among them is tyrosine, which is then carried by the bloodstream to the brain and transformed into dopamine. The tiny sub- group of neurons (less than 0.01%) that use dopamine to link up with the rest of the brain forms a kind of network called the mesolimbic pathway. It is the brain’s reward system, rooted in the midbrain and branching out into the forebrain and frontal lobes.

When these reward neurons become activated, they release the dopamine that regulates our mood and rewards our attention. It is the microscopic engine behind our species’ macroscopic passions: it drives curiosity, fascination, and that uniquely human behavior: aesthetic contemplation.

Synapsis Illustration by Marco SerrotMD

Synapsis Illustration by Marco SerrotMD

As an ophthalmologist, this is something I have studied for forty years. Or perhaps I should say the last sixty years?.

I’ve been an artist as long as I can remember. And as leading neuroscientists have proposed, artists might be considered intuitive pragmatic researchers of the visual brain.

I grew up in the oldest part of my hometown in Mexico. My childhood memories are dominated by the alluring scent of oil paint and turpentine in my mother’s painting corner and the severity of the India ink, the square rulers, and the two drawing tables in my father’s drafting studio that occupied the space where a dining table should be.

It was only natural for me to play with my parents “toys.” Or at least some of them. As a young child, I would spend much of my time at home doodling and coloring—unknowingly more so than most other children.

It was only as an adult that I came to recognize that this exuberant childhood obsession had a deep neurochemical commonality with many addictive thrills: The high one feels when hours of practicing a craft pay off with a feeling of mastery on the positive side--or just as well on the negative: the helpless compulsion of the gambling addict who keeps playing after a losing streak. I was surprised to learn that our dopaminic brain modules reward profitable behaviors that lead to the best individual and collective humane achievements and paradoxically also nourishes our darkest flaws.

My addiction happily, was advantageous. I grew up a natural visual learner —a great asset for a child’s intellectual development. Throughout elementary school, I was a straight-A student (Not even one A- in any subject!) I can hardly take credit for this since no special effort was necessary. Learning came naturally and was extremely enjoyable. Schoolwork was easy for me. On school day afternoons, homework was quickly dispatched, and I would then spend hours devouring encyclopedias and atlases far beyond school requirements.

All this had an unexpected and unintended consequence. My father decided a career in the arts would be a waste of my good grades (and shame for my family). He thus prohibited my frequent visits to the artist atelier a few doors down, where at age 9 art students would let me in to play with discarded paints and canvases. I never got to go back there, and even at home, my mother’s painting materials were mostly kept out of reach. Fortunately, I was able to find a place where my talents were encouraged: I became the official interior designer of my classroom, covering walls and bulletin boards with drawings and paintings of arthropods, legumes, and continents. School teachers did all they could to have me in their homeroom groups. They knew this would mean having the best-looking classroom spaces.

When the time came to choose a profession, my father, a famously strict topography professor at the State University, adamantly insisted that I study civil engineering. Out of some natural rebellious impulse, I disobeyed and signed up for medical school, and it was in my second year that I discovered the physiology of the eye and its relationship to the nature of light. This turned my life around. Not only was I a maker of images, but I was also now coming to understand the way images are registered by the eye and processed by the brain. I specialized in ophthalmology, and after completing advanced studies abroad, I became a professor, medical faculty chair, and director of the clinical department of neuro-ophthalmology.

By accident and serendipity, I found myself orbiting around two suns separated by millions of light years: I had created my own binary star solar system of art and science.

- Marco Serrot MD -